I am the servant of the one who steals a heart, Or falls in love with the one who gives life. He who is neither lover nor beloved, May not be found in the realm of God. Saadi

Muslih-ud-Din Mushrif ibn-Abdullah Shirazi - His pen name is Saadi Shirazi

Abū-Muhammad Muslih al-Dīn bin Abdallāh Shīrāzī (Persian: ابومحمد مصلحالدین بن عبدالله شیرازی), better known by his pen-name Saadi (سعدی Saʿdī(![]() Sa'di (help·info))), also known as Saadi of Shiraz (سعدی شیرازیSaadi Shirazi), was a major Persian poet and prose writer of the medieval period. He is recognized for the quality of his writings and for the depth of his social and moral thoughts. Saadi is widely recognized as one of the greatest poets of the classical literary tradition, earning him the nickname "Master of Speech" (استاد سخن) or "The Master" among Persian scholars. He has been quoted in the Western traditions as well. Bustan is considered one of the 100 greatest books of all time according to The Guardian. His other writing a story tale is called Gulistan.

Sa'di (help·info))), also known as Saadi of Shiraz (سعدی شیرازیSaadi Shirazi), was a major Persian poet and prose writer of the medieval period. He is recognized for the quality of his writings and for the depth of his social and moral thoughts. Saadi is widely recognized as one of the greatest poets of the classical literary tradition, earning him the nickname "Master of Speech" (استاد سخن) or "The Master" among Persian scholars. He has been quoted in the Western traditions as well. Bustan is considered one of the 100 greatest books of all time according to The Guardian. His other writing a story tale is called Gulistan.

Saadi was born in Shiraz, Iran, according to some, shortly after 1200, according to others sometime between 1213 and 1219. In the Golestan, composed in 1258, he says in lines evidently addressed to himself, "O you who have lived fifty years and are still asleep"; another piece of evidence is that in one of his qasida poems he writes that he left home for foreign lands when the Mongols came to his homeland Fars, an event which occurred in 1225.

It seems that his father died when he was a child. He narrates memories of going out with his father as a child during festivities.

After leaving Shiraz he enrolled at the Nizamiyya University in Baghdad, where he studied Islamic sciences, law, governance, history, Arabic literature, and Islamic theology; it appears that he had a scholarship to study there. In the Golestan, he tells us that he studied under the scholar Abu'l-Faraj ibn al-Jawzi (presumably the younger of two scholars of that name, who died in 1238).

In the Bustan and Golestan Saadi tells many colourful anecdotes of his travels, although some of these, such as his supposed visit to the remote eastern city of Kashgar in 1213, may be fictional. The unsettled conditions following the Mongol invasion of Khwarezm and Iran led him to wander for thirty years abroad through Anatolia (where he visited the Port of Adana and near Konya met ghazi landlords), Syria (where he mentions the famine in Damascus), Egypt (where he describes its music, bazaars, clerics and elites), and Iraq (where he visits the port of Basra and the Tigris river). In his writings he mentions the qadis, muftis of Al-Azhar, the grand bazaar, music and art. At Halab, Saadi joins a group of Sufiswho had fought arduous battles against the Crusaders. Saadi was captured by Crusaders at Acre where he spent seven years as a slave digging trenches outside its fortress. He was later released after the Mamluks paid ransom for Muslim prisoners being held in Crusader dungeons.

Saadi visited Jerusalem and then set out on a pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina. It is believed that he may have also visited Oman and other lands in the south of the Arabian Peninsula.

Because of the Mongol invasions he was forced to live in desolate areas and met caravans fearing for their lives on once-lively silk trade routes. Saadi lived in isolated refugee camps where he met bandits, Imams, men who formerly owned great wealth or commanded armies, intellectuals, and ordinary people. While Mongol and European sources (such as Marco Polo) gravitated to the potentates and courtly life of Ilkhanate rule, Saadi mingled with the ordinary survivors of the war-torn region. He sat in remote tea houses late into the night and exchanged views with merchants, farmers, preachers, wayfarers, thieves, and Sufi mendicants. For twenty years or more, he continued the same schedule of preaching, advising, and learning, honing his sermons to reflect the wisdom and foibles of his people. Saadi's works reflect upon the lives of ordinary Iranians suffering displacement, agony and conflict during the turbulent times of the Mongol invasion.

Saadi Shirazi is welcomed by a youth from Kashgar during a forum in Bukhara.

Saadi mentions honey-gatherers in Azarbaijan, fearful of Mongol plunder. He finally returns to Persia where he meets his childhood companions in Isfahan and other cities. At Khorasan Saadi befriends a Turkic Emir named Tughral. Saadi joins him and his men on their journey to Sindh where he meets Pir Puttur, a follower of the Persian Sufi grand master Shaikh Usman Marvandvi (1117–1274).

He also refers in his writings about his travels with a Turkic Amir named Tughral in Sindh (Pakistan across the Indus and Thar), India (especially Somnath, where he encounters Brahmans), and Central Asia (where he meets the survivors of the Mongol invasion in Khwarezm). Tughral hires Hindu sentinels. Tughral later enters service of the wealthy Delhi Sultanate, and Saadi is invited to Delhi and later visits the Vizier of Gujarat. During his stay in Gujarat, Saadi learns more about the Hindus and visits the large temple of Somnath, from which he flees due to an unpleasant encounter with the Brahmans. Katouzian calls this story "almost certainly fictitious".

Saadi came back to Shiraz before 1257 CE / 655 AH (the year he finished composition of his Bustan). Saadi mourned in his poetry the fall of Abbasid Caliphate and Baghdad's destruction by Mongol invaders led by Hulagu in February 1258.

When he reappeared in his native Shiraz, he might have been in his late forties. Shiraz, under Atabak Abubakr ibn Sa'd ibn Zangi (1231–60), the Salghurid ruler of Fars, was enjoying an era of relative tranquility. Saadi was not only welcomed to the city but was shown great respect by the ruler and held to be among the greats of the province. Some scholars believe that Saadi took his nom de plume (in Persian takhallos) from the name of Abubakr's son, Sa'd, to whom he dedicated the Golestan; however, Katouzian argues that it is likely that Saadi had already taken the name from Abubakr's father Sa'd ibn Zangi (d. 1226). Some of Saadi's most famous panegyrics were composed as a gesture of gratitude in praise of the ruling house and placed at the beginning of his Bustan. The remainder of Saadi's life seems to have been spent in Shiraz.

The traditional date for Saadi's death is between 1291 and 1294

Bustan and GulistaN

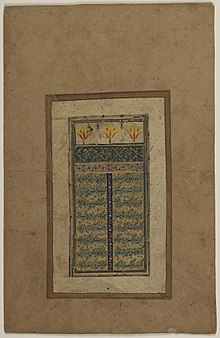

The first page of Bustan, from a Mughal manuscript.

Sa'di's best known works are Bustan (The Orchard) completed in 1257 and Gulistan (The Rose Garden) completed in 1258. Bustan is entirely in verse (epic metre). It consists of stories aptly illustrating the standard virtues recommended to Muslims (justice, liberality, modesty, contentment) and reflections on the behavior of dervishes and their ecstatic practices. Gulistan is mainly in prose and contains stories and personal anecdotes. The text is interspersed with a variety of short poems which contain aphorisms, advice, and humorous reflections, demonstrating Saadi's profound awareness of the absurdity of human existence. The fate of those who depend on the changeable moods of kings is contrasted with the freedom of the dervishes.

Regarding the importance of professions Saadi writes:

O darlings of your fathers, learn the trade because property and riches of the world are not to be relied upon; also silver and gold are an occasion of danger because either a thief may steal them at once or the owner spend them gradually; but a profession is a living fountain and permanent wealth; and although a professional man may lose riches, it does not matter because a profession is itself wealth and wherever you go you will enjoy respect and sit on high places, whereas those who have no trade will glean crumbs and see hardships.

Saadi is also remembered as a panegyrist and lyricist, the author of a number of odes portraying human experience, and also of particular odes such as the lament on the fall of Baghdad after the Mongol invasion in 1258. His lyrics are found in Ghazaliyat (Lyrics) and his odes in Qasa'id (Odes). He is also known for a number of works in Arabic.

In the Bustan, Saadi writes of a man who relates his time in battle with the Mongols:

In Isfahan I had a friend who was warlike, spirited, and shrewd....after long I met him: "O tiger-seizer!" I exclaimed, "what has made thee decrepit like an old fox?"

He laughed and said: "Since the days of war against the Mongols, I have expelled the thoughts of fighting from my head. Then did I see the earth arrayed with spears like a forest of reeds. I raised like smoke the dust of conflict; but when Fortune does not favour, of what avail is fury? I am one who, in combat, could take with a spear a ring from the palm of the hand; but, as my star did not befriend me, they encircled me as with a ring. I seized the opportunity of flight, for only a fool strives with Fate. How could my helmet and cuirass aid me when my bright star favoured me not? When the key of victory is not in the hand, no one can break open the door of conquest with his arms.

The enemy were a pack of leopards, and as strong as elephants. The heads of the heroes were encased in iron, as were also the hoofs of the horses. We urged on our Arab steeds like a cloud, and when the two armies encountered each other thou wouldst have said they had struck the sky down to the earth. From the raining of arrows, that descended like hail, the storm of death arose in every corner. Not one of our troops came out of the battle but his cuirass was soaked with blood. Not that our swords were blunt—it was the vengeance of stars of ill fortune. Overpowered, we surrendered, like a fish which, though protected by scales, is caught by the hook in the bait. Since Fortune averted her face, useless was our shield against the arrows of Fate.

Other works

In addition to the Bustan and Gulistan, Saadi also wrote four books of love poems (ghazals), and number of longer mono-rhyme poems (qasidas) in both Persian and Arabic. There are also quatrains and short pieces, and some lesser works in prose and poetry.Together with Rumi and Hafez, he is considered one of the three greatest ghazal-writers of Persian poetry.

Bani Adam

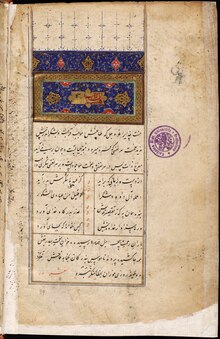

A copy of Saadi Shirazi's works by the Bosniak scholar Safvet beg Bašagić (1870–1934)

Saadi is well known for his aphorisms, the most famous of which, Bani Adam, is part of the Gulistan. In a delicate way it calls for breaking down all barriers between human beings:

بنى آدم اعضای یک پیکرند

که در آفرینش ز یک گوهرندچو عضوى بدرد آورَد روزگار

دگر عضوها را نمانَد قرارتو کز محنت دیگران بی غمی

نشاید که نامت نهند آدمی

banī ādam a'zā-ye yek peykar-andke dar āfarīn-aš ze yek gowhar-andčo 'ozvī be dard āvarad rūzgārdegar 'ozvhā-rā na-mānad qarārto k-az mehnat-ē dīgarān bīqam-īna-šāyad ke nām-at nahand ādamī

The literal translation of the above is as follows:

"The children of Adam are the members of one body,

and are from the same essence in their creation.

When the conditions of the time hurt one of these members,

other members will suffer from discomfort.

If you are indifferent to the misery of others,

it is not fitting that they should call you a human being."

The above version with yekdīgar "one another" is the usual one quoted in Iran (for example, in the well-known edition of Mohammad Ali Foroughi, on the carpet installed in the United Nations building in New York in 2005, and on the back of the 100,000-rial banknote issued in 2010); according to the scholar Habib Yaghmai is also the only version found in the earliest manuscripts, which date to within 50 years of the writing of the Golestan. Some books, however, print a variation banī ādam a'zā-ye yek peykar-and ("The sons of Adam are members of one body"), and this version, which accords more closely with the hadith quoted below, is followed by most English translations.

The following translation is by H. Vahid Dastjerdi:

Adam's sons are body limbs, to say;

For they're created of the same clay.

Should one organ be troubled by pain,

Others would suffer severe strain.

Thou, careless of people's suffering,

Deserve not the name, "human being".

This is a verse translation by Ali Salami:

Human beings are limbs of one body indeed;

For, they’re created of the same soul and seed.

When one limb is afflicted with pain,

Other limbs will feel the bane.

He who has no sympathy for human suffering,

Is not worthy of being called a human being.

And by Richard Jeffrey Newman:

All men and women are to each other

the limbs of a single body, each of us drawn

from life’s shimmering essence, God’s perfect pearl;

and when this life we share wounds one of us,

all share the hurt as if it were our own.

You, who will not feel another’s pain,

you forfeit the right to be called human.

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said in Tehran: "[...] At the entrance of the United Nations there is a magnificent carpet – I think the largest carpet the United Nations has – that adorns the wall of the United Nations, a gift from the people of Iran. Alongside it are the wonderful words of that great Persian poet, Sa’adi":

All human beings are members of one frame,

Since all, at first, from the same essence came.

When time afflicts a limb with pain

The other limbs at rest cannot remain.

If thou feel not for other’s misery

A human being is no name for thee. [...][

According to the former Iranian Foreign Minister and Envoy to the United Nations, Mohammad Ali Zarif, this carpet, installed in 2005, actually hangs not in the entrance but in a meeting room inside the United Nations building in New York.

The verses are believed to have been inspired by a Hadith, or saying, of the Prophet Mohammed in which he says: “The example of the believers (Muslims) in their affection, mercy, and compassion for each other is that of a body. When any limb aches, the whole body reacts with sleeplessness and fever.

Legacy and poetic style

Saadi distinguished between the spiritual and the practical or mundane aspects of life. In his Bustan, for example, spiritual Saadi uses the mundane world as a spring board to propel himself beyond the earthly realms. The images in Bustan are delicate in nature and soothing. In the Gulistan, on the other hand, mundane Saadi lowers the spiritual to touch the heart of his fellow wayfarers. Here the images are graphic and, thanks to Saadi's dexterity, remain concrete in the reader's mind. Realistically, too, there is a ring of truth in the division. The Sheikh preaching in the Khanqah experiences a totally different world than the merchant passing through a town. The unique thing about Saadi is that he embodies both the Sufi Sheikh and the travelling merchant. They are, as he himself puts it, two almond kernels in the same shell.

Saadi's prose style, described as "simple but impossible to imitate" flows quite naturally and effortlessly. Its simplicity, however, is grounded in a semantic web consisting of synonymy, homophony, and oxymoron buttressed by internal rhythm and external rhyme.

Chief among these works is Goethe's West-Oestlicher Divan. Andre du Ryer was the first European to present Saadi to the West, by means of a partial Frenchtranslation of Gulistan in 1634. Adam Olearius followed soon with a complete translation of the Bustan and the Gulistan into German in 1654.

In his Lectures on Aesthetics, Hegel wrote (on the Arts translated by Henry Paolucci, 2001, p. 155–157):

Pantheistic poetry has had, it must be said, a higher and freer development in the Islamic world, especially among the Persians ... The full flowering of Persian poetry comes at the height of its complete transformation in speech and national character, through Mohammedanism ... In later times, poetry of this order [Ferdowsi's epic poetry] had a sequel in love epics of extraordinary tenderness and sweetness; but there followed also a turn toward the didactic, where, with a rich experience of life, the far-traveled Saadi was master before it submerged itself in the depths of the pantheistic mysticism taught and recommended in the extraordinary tales and legendary narrations of the great Jalal-ed-Din Rumi.

Alexander Pushkin, one of Russia's most celebrated poets, quotes Saadi in his work Eugene Onegin, "as Saadi sang in earlier ages, 'some are far distant, some are dead'. Gulistan was an influence on the fables of Jean de La Fontaine. Benjamin Franklin also in one of his works, DLXXXVIII A parable on Persecution, quotes one of Bustan of Saadi's parable, apparently without knowing the source. Ralph Waldo Emerson was also interested in Sadi's writings, contributing to some translated editions himself. Emerson, who read Saadi only in translation, compared his writing to the Bible in terms of its wisdom and the beauty of its narrative.